Kristýna Brázdová se ve svém eseji zamýšlí nad autorským projevem významného kameramana (nejen) Československé nové vlny Jaroslava Kučery. Text zveřejňujeme v původním anglickém znění, jelikož vznikl v rámci autorčina studijního pobytu na polské filmové škole Krzysztof Kieślowski Film School.

„Ale mě strašně zajímá vyzkoušet jednou možnost vytvořit z filmového obrazu docela

autonomní záležitost, jež by se vymykala z konvenčního pojetí filmu. Jde o to, zda ve filmu

vytváříme jenom více či méně krásné pohyblivé obrazy něčeho, nebo zda by tyto obrazy

mohly být samy nositeli významu, sdělovat něco nikoli objektivně, nýbrž subjektivně. Prostě

udělat s filmem pokus na takové úrovni, kde je už dávno doma moderní malířství, poezie,

hudba. Vytvořit novou soustavu sdělovacích prostředků filmu.“ (Hames 2008, 213)

(I am really interested in trying to create a sense of autonomy of the film image one day, in a

way that would differ from the conventional approach to film. The thing with films is – are we

just creating more or less beautiful moving images of something? Or could those pictures

hold meaning on their own? Telling something not objectively, but subjectively. We could just

experiment with film on a level which modern painting, poetry or music has already reached.

We could create new means of communication in film.)

It’s strange to write about cinematography, the result of a cinematographer’s work, without

using image to prove a point. I can try my best to describe what I saw but still it can be just a

shadow of what the image actually looked like. Because unlike in the Scripture, in the

beginning of a film, there were no words, there were pictures. The relationship between a

screenplay and images is something that I am trying to understand these days. A film can

start as a series of visions inside the director’s or screenwriter’s head. Then it gets clumsily

translated to words that somehow have to evoke the original vision that is then produced by

a cinematographer and the whole team of people that create a moving picture. At least that’s

how I have always imagined it. But during my stay in Katowice I finally started to understand

what goes into the work of a cinematographer.

It’s not just about fulfilling someone’s vision, it is also about having a vision of your own. And

that is quite hard to hear on the other side, by the writing table. Do the words actually matter

if they won’t be followed in the end? I don’t know the answer to that question. Also I don’t

know if my words matter at all. But I have to admit, that it’s the cinematographer’s and

costume designer’s work that brought me to studying screenwriting after all.

When I was deciding where to go to university, I abandoned my years-long plan of going to a

diplomatic career and realised that I want to pursue art. I was torn between fine arts and

literature. And when I saw Sedmikrásky, Valérie a týden divů and In the Mood for Love, I

came to a conclusion that I can have both, if I choose to study film, if I choose to study

screenwriting. The visual aspect that I wasn’t used to from „normal“ films was what spoke to

me. And it feels like a full circle trying to understand what is behind those images.

I chose to write my essay about Jaroslav Kučera, one of the most important

cinematographers of Czechoslovak New Wave. He collaborated with many different directors

such as Jan Němec, Věra Chytilová, Jaromil Jireš, Vojtěch Jasný or Juraj Herz. The usual

approach when trying to analyse a film is to try to distinguish a specific style of the director.

But looking at the cinematographer’s side can help us suddenly see the unique ideas that

he’s bringing to the works of different directors. If he had worked in an artistic tandem it could

be much harder to realise if it is just the style of the director or of the cinematographer, I

think.

Over the course of his life, Jaroslav Kučera was part of many projects, so I decided to focus

only on one of them – Až přijde kocour (1963, dir. Vojtěch Jasný). There are many significant

films that he worked on but I chose this one because it is probably the first of Kučera’s

experiments with colour (that he later developed more while working on Chytilová’s

Sedmikrásky, for example) (Hames 2008, 67). I would also say that many examples of his

strengths can be found in this film therefore I can demonstrate them on stills from it.

Because I realised that one image in such a case really speaks more than a thousand

words.

The film Až přijde kocour (The Cassandra Cat) tells a lyrical story of villagers that are taken

by surprise by a visit of a wizard, an acrobat and a magical cat. The cat can make people

appear literally in their true colours – purple representing hypocrisy, yellow infidelity, grey

theft and red love. That is not appreciated by the local school’s director who is trying to get

rid of the cat. But the village’s children demand justice. The film is shot on colour film

material and the figures of people in certain scenes are colourized in post production. That is

one of the most distinctive visual elements of the film. But the film also shows other

interesting features that indicate Kučera’s talents.

The very first shot shows us children’s painting of the village on the wall. It gives us a hint

about the location of the story and also indicates that children and their pictures are going to

play an important part in the story. We can see that later in the film when the camera shows

us how children at school paint according to their fantasy during Jan Werich’s character’s

story-telling. I would say that this shot also speaks about Kučera’s sensitivity to different

textures that is visible in his other works, too.

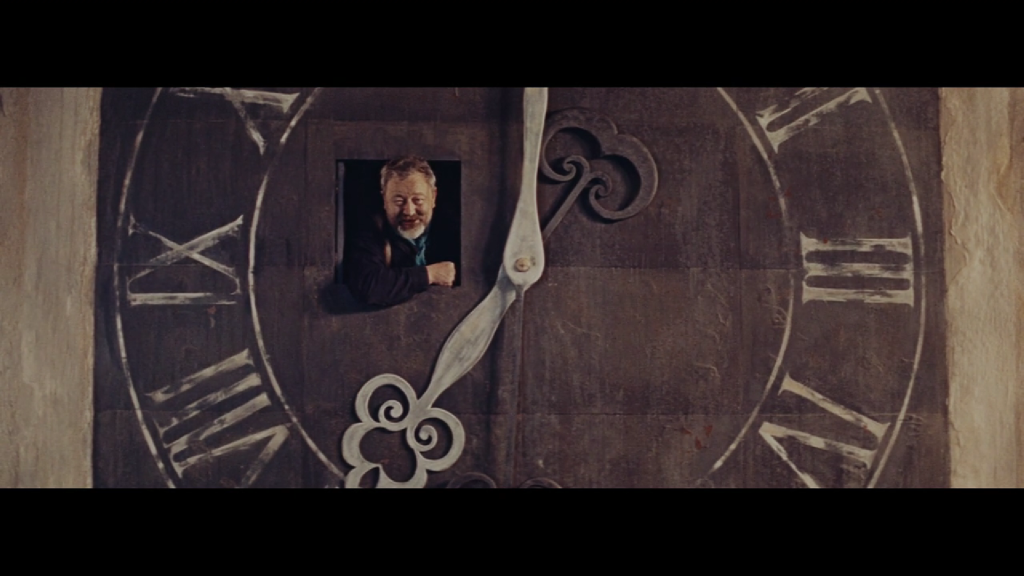

Another shot depicts the narrator of the whole story, Mr Oliva played by a legendary Czech

actor Jan Werich. He looks out of the clock from the top of the village tower. He, as the

narrator, has an overlook of the whole main square and later introduces us to all of the main

characters. But the term main character is kind of problematic with this film because, like in

many other Czech and Slovak films of this period, there is a so-called „collective hero“,

which basically means that the story focuses on a group or more groups of people (Hames

2008, 68). I decided to include this shot in particular because I think it’s a very unexpected

and entertaining way to introduce the narrator. It can be also seen as a nod to the silent film

Safety Last! (1923), in my opinion.

This still represents the main part of the exposition where Mr Oliva describes the villagers

and we see them through his point of view. The image is slightly blurred as he is watching

them with a magnifying glass.

A key element that is characteristic for this film are shots of birds in the sky. They represent

freedom which is one the main topics of the film. The symbol of birds is used on many

occasions in the film and the meaning slightly changes each time depending on the context.

I think that this can be seen as the example of Kučera’s attempts to use images that hold

their own meaning. Also the fact that it’s not just any bird, it’s a stork to be exact, is quite

important. The story takes place in the Vysočina Region, in particular in a historical town

called Telč where the director Jasný comes from. And storks are very common in this area. I

used to come to Telč every year with my grandparents because we spent summer in the

region and the storks are pretty much a symbol of my time there. On our way there we would

look out of the car to see them nesting on high chimneys and we would try to count how

many little ones they had. I think that sensitivity to such things speaks volumes about

Kučera’s and Jasný’s approach to filmmaking.

This shot is one of several that use something (partly) transparent to adjust our view on

something. Like in this case, we see the square blurred by the rain on a window. Or later,

when we are in some sort of a tent for the performers and the walls of the tent are made

from a see-through green fabric. Or in a scene where a girl paints a cat on a window in a

shop and we see her through the painted window. I think that’s a really nice play with depth

of field and also with textures in this shot in the picture.

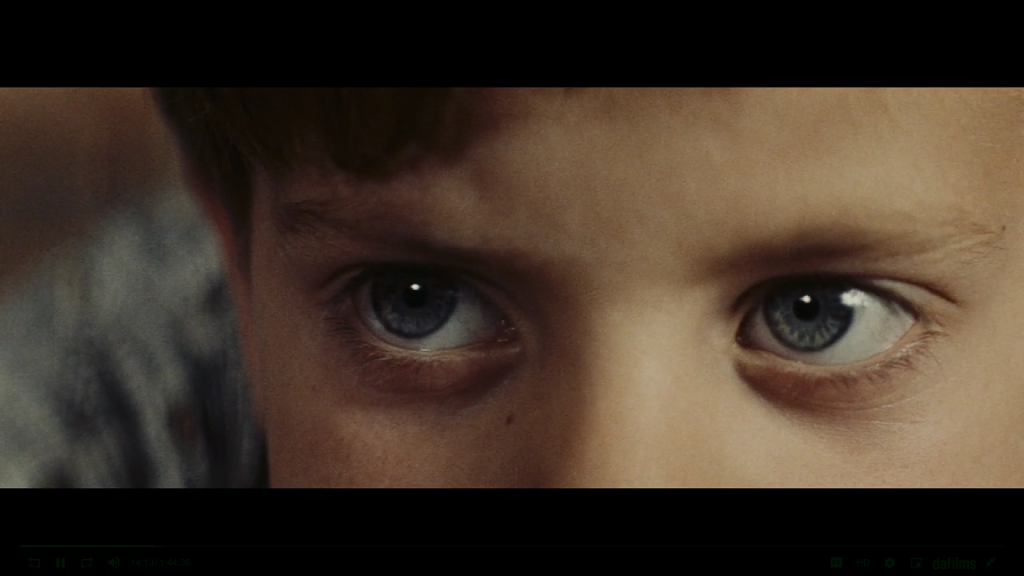

In this scene we are in a classroom where Mr Robert, one of the most important characters,

teaches. We can hear the children’s whispering and the camera focuses on close-ups of

their faces. We get closer to them so it’s not just an anonymous crowd that keeps the plot

moving later on. We get to know them more personally.

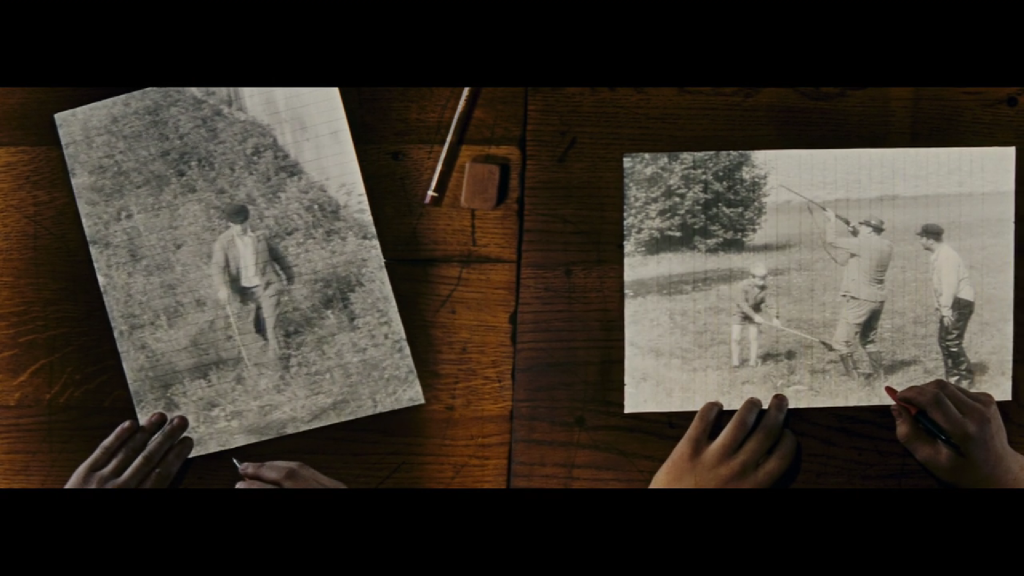

Similar thing happens when Mr Robert tells them to draw what they like or dislike about their

town or what they would like to change about the place where they live. In the sound we

hear the children’s thoughts about what they dislike about things that their parents or fellow

residents do. And Jaroslav Kučera decided to do an interesting thing by showing little scenes

from the village on children’s blank pages so we clearly see what they are thinking about.

The children, unlike many of the adults in this film, still believe in ideals such as friendship,

honesty and truth. And they have their inner sense for justice that their teacher Mr Robert is

trying to support, but many other characters including some of their own parents or the

school’s director are doing the contrary.

With this still I decided to include one of the most captivating scenes where the janitor and

also the dogbody of the school director brings stuffed stork that the director had previously

killed. The director tells the janitor to make it fly which starts a crazy camera ride as he runs

around in circles around the director, his wife and his secretary. The scene (accompanied by

cheerful music) has a lot of irony to it. The office is also decorated with purple curtains which

gives us a hint about which colour is going to turn the director and his friends.

After the crazy ride comes a scene that is very much in contrast with the previous one. Mr

Oliva is supposed to be a model for the children to paint but he tells them a story instead and

the children decide to paint what he is talking about. From a cinematography point of view,

this scene is important to me, because there are no special effects just for the sake of it.

Kučera leaves a room for the actor to be the main focus of this scene. And it really works

because Jan Werich is a great story-teller (he also helped to write parts of the script) and he

steals the show in a good way.

This scene is unlike anything I’ve seen in a cinema. It takes place after the arrival of the

circus performers to the village. They create a spectacle in the courtyard of the local chateau

that is quite eye-opening for the villagers because it reflects their own life. The scene was

done with a group of actual mimes and the clothing silhouettes on a dark background create

a fascinating view. In this picture in particular there are white silhouettes of birds again

created with the hands of the performers.

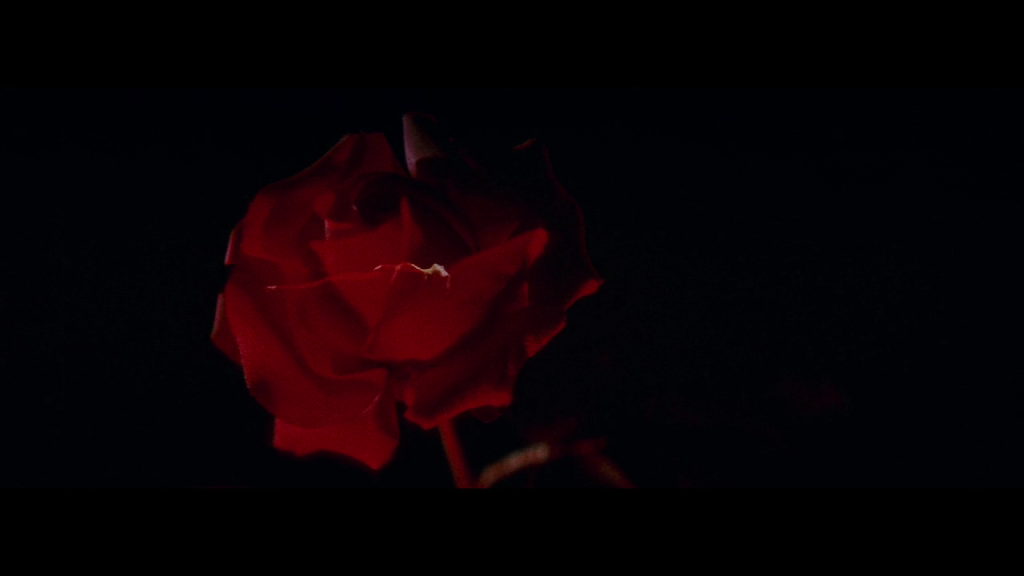

With this still I would like to demonstrate one of other elements that Kučera uses. He blends

two shots together and creates a new meaning for them. Here we can see a rose that

symbolises the people who are filled with love. And the picture gets transformed into the

silhouette of the acrobat dressed in a red costume. Similar technique is used also later when

Kučera blends together several different shots of renaissance houses on the main square.

Here is an example of the colourized figures that appear after the magical cat looks at them.

Kučera experimented with colour also later in his career, for example in Chytilová’s

Sedmikrásky and also later in Noc na Karlštejně for example, in one of the most famous

scenes. Kučera also had an archive of his diary or „home videos“ where he was trying some

of his experiments (“Co říká deník Jaroslava Kučery o jeho tvorbě a životě s Věrou

Chytilovou” 2019, Respekt). I decided to include more stills from this scene because apart

from the colourisation, lighting and composition plays an important role as well.

And here we can see one of the characters that is moving and turning purple but we can see

parts of red as well. That suggests the character development that she undergoes later in

the story. Similar visual experiments Kučera also applied for example in Sedmikrásky or in

hallucination scenes in Morgiana (1972).

In the above picture and also in the two following I wanted to demonstrate Kučera’s

sensitivity to natural light. This sensitivity is also visible in garden scenes in Morgiana, for

example. This first one is especially interesting to me because as Diana, the acrobat

character, moves the umbrella against the sun, the light shines through and gives her face a

red shadow even without colourisation in post production.

In one of the dream-like scenes, Mr Robert and Diana run through the fields, filled with

happiness. In this particular shot we can see Kučera’s ability to capture natural landscapes

that was also influenced by another important Czech cinematographer Jan Stallich (Hames

2008, 35). This ability is also visible in another Jasný’s film where Kučera was as a DOP, in

Všichni dobří rodáci. The way the edges of the hills are glowing with warm light reminds of

paintings of Joseph Rebell.

At the end I wanted to include four shots that capture the unique architecture and

atmosphere of Telč in different lighting situations. The one above where children paint the

cat on rooftops reminds me of another Czechoslovak New Wave film called Slnko v sieti that

has a similar lyrical approach and also some scenes take place on rooftops (just not in Telč,

but in Bratislava instead).

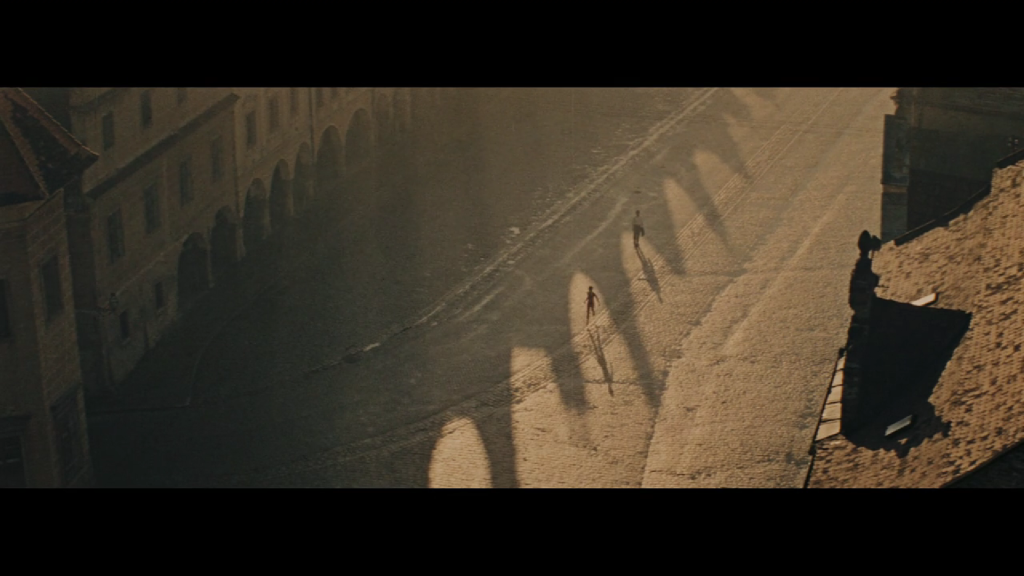

I think that Kučera decided to use many shots from a bird’s eye perspective not only to show

us the interesting location but also to give us a broader perspective on the characters and

their conflicts. When people get too caught up in their daily troubles and arguments it’s

sometimes really hard to see the bigger picture and realise what actually matters in life. And

it’s a great opportunity to use film as a medium to show that. This perspective is also

connected to the symbols of birds that are used throughout the film. They look down on the

people and their struggles, just like the narrator when he’s watching them from the tower. But

he also becomes one of the characters, he is also part of the story that he is telling, only the

birds remain above, unless some of the villagers decide to shoot them.

To conclude, I would like to mention that this film is an example of the legacy of the First

Republic period (1918 – 1938) that was one of the most important cultural periods of modern

day Czechia. During this time, there was the artistic style called poetism and in my opinion

this film brings to attention several key elements of this style and in a way tries to continue

the artistic movement established several decades earlier (as the development was

interrupted by the Second World War). Those elements include inspiration in folk

entertainment, lyrical and playful approach to life and happiness found in ordinary things.

Another way in which the First Republic legacy is presented is through the casting of Jan

Werich who was (along with Jiří Voskovec) one of the most important figures in satirical

theatre. The musical and less narrative parts of the film also take inspiration in revue style

performances from theatre, in my opinion.

I feel the need to mention that even though Kučera’s imagery is very fascinating and holds a

meaning, I can’t help myself thinking that what brings another layer of subjectivity to the film

is its sound. Be it through music, dialogues or sound effects, it’s hard to imagine the film

without it. It reminds me of an interview that I had with one director that I included in my

bachelor’s thesis. He shared with me his experience that the viewer has a tendency to

perceive a picture as pure information and the sound is what adds the emotional layer to it

(Brázdová 2022, JAMU). I agree with him and I think that the importance of sound can be

often underestimated.

I wonder if Kučera actually reached his goal that he mentions in the quote at the beginning of

my essay. With visual aspects (but not just with them, but also with art in general) there is

always the risk that we create beautiful pictures and special effects just for the sake of it and

we lose track of the meaning. In my opinion, despite many of Kučera’s innovative ideas, his

imagery still stays true to the meaning of the film. But there is always the risk that it won’t be

perceived that way. He personally described the case of Sedmikrásky, where he had his

artistic vision but the aesthetic of the film started to develop on its own during shooting and

also after the film was finished (Hames 2008, 211). And from my own experience, I am not

sure how many people who see Sedmikrásky or any other very visually unique film enjoy it

as the colourful and crazy fun that it seems to be and how many actually search for the

meaning behind it. Both Chytilová and Kučera wanted an active viewer that finds his own

understanding of the film. But when I saw it for the first time, I wouldn’t describe myself as an

active viewer, I was just in awe that such a film exists and that was it. Maybe the words

matter in the end. Or maybe one has to train himself or herself to look at pictures and also

see behind them.

That brings me to another point which is the Kučera’s influence in today’s cinematography or

more the lack thereof. When I look at famous Czech films from the 60s to the 70s (Hames

2008, 98) but also from the First Republic period, there was a strong line of lyrical films that

were not afraid to disattach from realism while still remaining relevant to reality. Maybe I’m

wrong but I feel like Czech contemporary film is missing this approach. And while Kučera’s

work is certainly not forgotten (he had an exhibition in Dům umění in Brno in 2017 and there

is a book about him (“Jaroslav Kučera: kameraman československé nové vlny | dafilms.cz”

2019)), I think that partly because of the Soviet invasion that interrupted cultural

development after 1968 and also due to commercialization of films after the Velvet

Revolution in 1989, we lost something that made Czech film unique. Maybe it’s time to think

about finding it again.